"Because I Said So" Is Inevitable: Why Strategic Leadership Sometimes Means Moving With Authority

Lesson 23 of 25 from podcast conversations with leaders who leave the world better than they found it

My sister Nancy swore she'd be a different kind of parent.

She'd explain everything to her daughter. Help her understand why rules exist. Build consensus through reasoning.

"Because I said so" was lazy parenting. Her kid would understand the logic behind every decision.

Then reality hit.

Exhaustion. Question number 37 of the day. A toddler who wasn't actually asking for information—she was testing boundaries.

And Nancy heard herself say it: "Because I said so."

Not because she'd given up on parenting well. But because she'd learned something about decision-making: sometimes efficiency trumps explanation.

Not everything requires consensus. Not everything needs extensive justification. Sometimes the most strategic thing a leader can do is make a clear decision and move.

The Consensus Trap

Mission-driven organizations love participatory decision-making.

We involve stakeholders. We seek input. We build consensus. We make sure everyone's voice is heard.

This is often valuable. Good participatory process creates buy-in. It surfaces perspectives you'd miss otherwise. It builds ownership.

But there's a shadow side: consensus culture can create analysis paralysis.

Every decision needs extensive discussion. Every change requires buy-in from everyone. Every pivot waits for universal agreement.

Meanwhile:

Opportunities close before you can decide

Problems escalate while you're building consensus

Staff get frustrated by the slowness

Competitors move faster

Sometimes the most strategic thing you can do is make a clear decision without consulting everyone.

Not because their input doesn't matter. But because not every decision requires it.

When Authority Serves Better Than Consensus

There are specific situations where moving with authority serves the organization better than building consensus:

Time-sensitive decisions: The opportunity window is closing. Waiting for consensus means missing it.

Operational decisions: How to organize the filing system doesn't need strategic discussion. Just decide and move on.

Decisions you'll learn from: Sometimes you need to try something to know if it works. Debating endlessly doesn't create clarity—action does.

When you have information others don't: As leader, you sometimes have context that's not appropriate or practical to share widely. You need to decide based on that context.

When consensus is impossible: Not every decision has a version that makes everyone happy. Waiting for universal agreement means never deciding.

When the decision is reversible: Low-stakes choices that can be adjusted if they don't work don't need extensive process.

In all these cases, clear direction serves the mission better than slow consensus.

The Decision Matrix

Here's how to tell which decisions need consensus and which need authority:

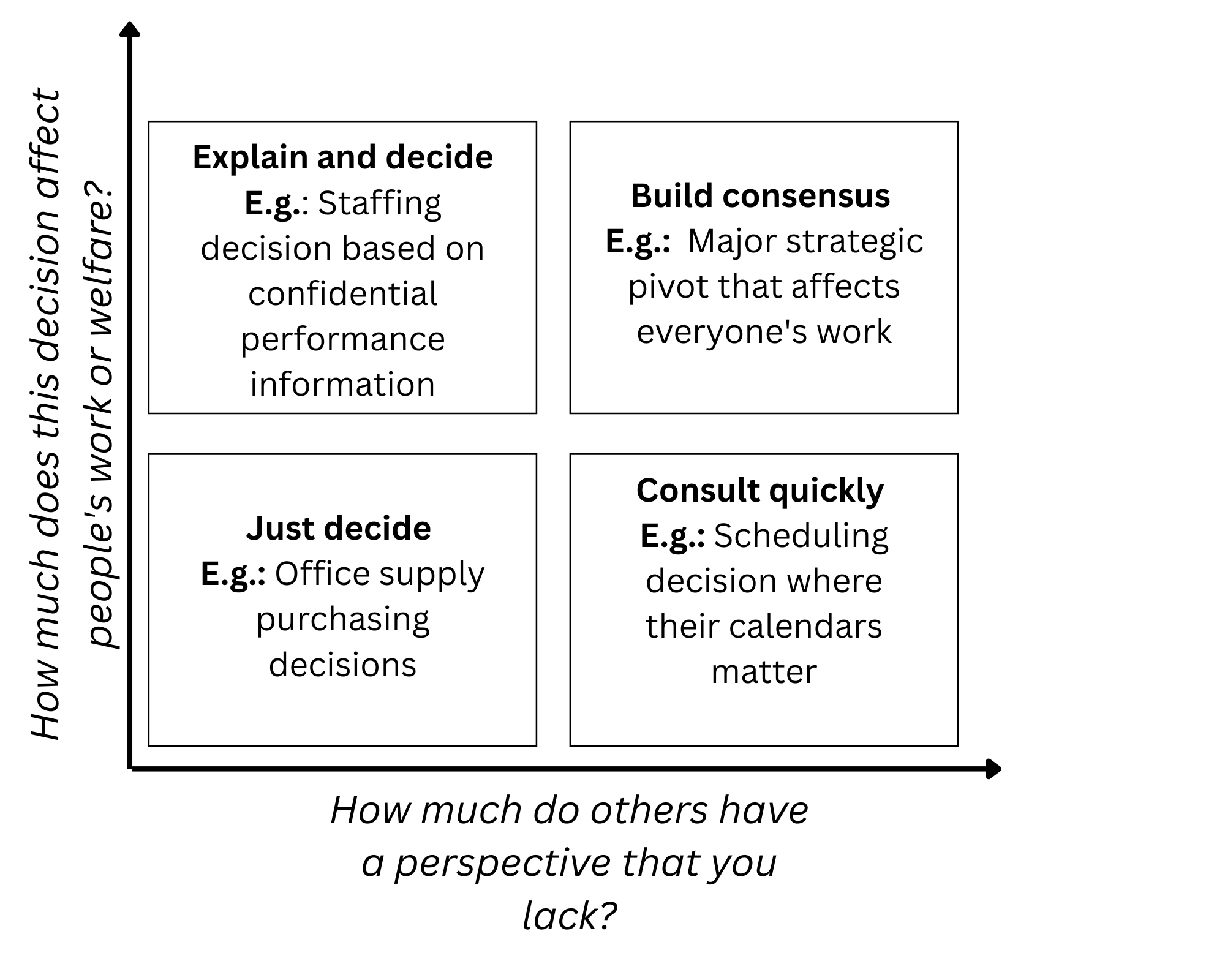

Ask two questions:

How much does this decision affect people's work or welfare?

How much do others have information or perspective you lack?

This creates four quadrants. The key is being strategic about which quadrant each decision falls into. Not treating everything like it requires consensus.

What Nancy Learned About Efficiency

Nancy's "because I said so" moment wasn't giving up on thoughtful parenting. It was recognizing that some questions don't require extensive explanation:

"Why do we have to leave the park now?"

Nancy could explain: "Because it's getting dark, we have dinner plans, you're getting tired even though you don't realize it, and I can see you're about to have a meltdown."

Or she could say: "Because I said so."

Both are valid parenting. The second is just more efficient.

Her daughter doesn't actually need to understand every decision. She needs to trust that Nancy is making good decisions for her.

The same applies to organizational leadership:

Your team doesn't need to understand every decision. They need to trust that you're making good decisions for the organization.

Sometimes the most respectful thing you can do is make a clear decision without requiring them to spend energy on something that's not their responsibility.

When To Explain And When To Decide

This doesn't mean abandoning participatory culture or becoming authoritarian. It means being strategic about when explanation serves and when it doesn't.

Always explain when:

The decision significantly affects people's work or wellbeing

You need their expertise or perspective to make a good decision

Buy-in is crucial for successful implementation

The decision sets precedent or reveals values

People are confused about direction and need clarity

Just decide when:

The decision is operational and reversible

You have context others don't have and can't share

The discussion would take more energy than the decision warrants

Speed matters more than perfection

You're the one accountable for the outcome

The skill is knowing the difference.

Why Leaders Avoid This

Many leaders—especially in mission-driven organizations—resist exercising decision authority:

Fear of seeming autocratic: "I don't want to be that kind of leader."

Commitment to equity: "Everyone's voice should matter."

Desire for buy-in: "They won't support decisions they weren't part of."

Lack of confidence: "What if I'm wrong?"

These are understandable concerns. But taken to extreme, they create dysfunction:

Leaders who won't make decisions without consensus slow the organization down.

Leaders who over-explain everything exhaust their teams.

Leaders who treat every decision as requiring input train teams to expect involvement in everything—which isn't sustainable or appropriate.

Strategic leadership requires knowing when to build consensus and when to move with clarity.

The Efficiency Question

Here's a practical test:

Look at your last ten organizational decisions. For each one, ask:

How much time did you spend building consensus versus how much was actually needed?

Were there decisions where extensive process added little value?

Were there decisions you could have made more quickly without undermining outcomes?

My guess is at least three of those ten could have been decided faster without loss of quality.

That's not about being less participatory. It's about being more strategic about where you invest process energy.

From Consensus To Strategic Authority

I'm not advocating for authoritarian leadership. Organizations that never consult their teams make terrible decisions.

I'm advocating for strategic authority: knowing when your job as leader is to make a clear decision without requiring consensus.

Nancy learned this with her toddler. Sometimes the answer is "because I said so" and that's fine.

Organizations need to learn the same lesson.

Not every decision requires extensive process. Sometimes the most strategic thing you can do is make a clear call and move forward.

Your team will respect that clarity more than they'll resent not being consulted on everything.

Next time you're about to launch into extensive consensus-building on a decision, ask:

Does this actually need consensus? Or am I just uncomfortable exercising authority?

If it's the second, try making a clear decision.

You might be surprised how much your team appreciates the clarity.

This is lesson 23 in a 25-part series exploring insights from podcast conversations with leaders who leave the world better than they found it.

Subscribe for weekly tools for strategic decision-making.